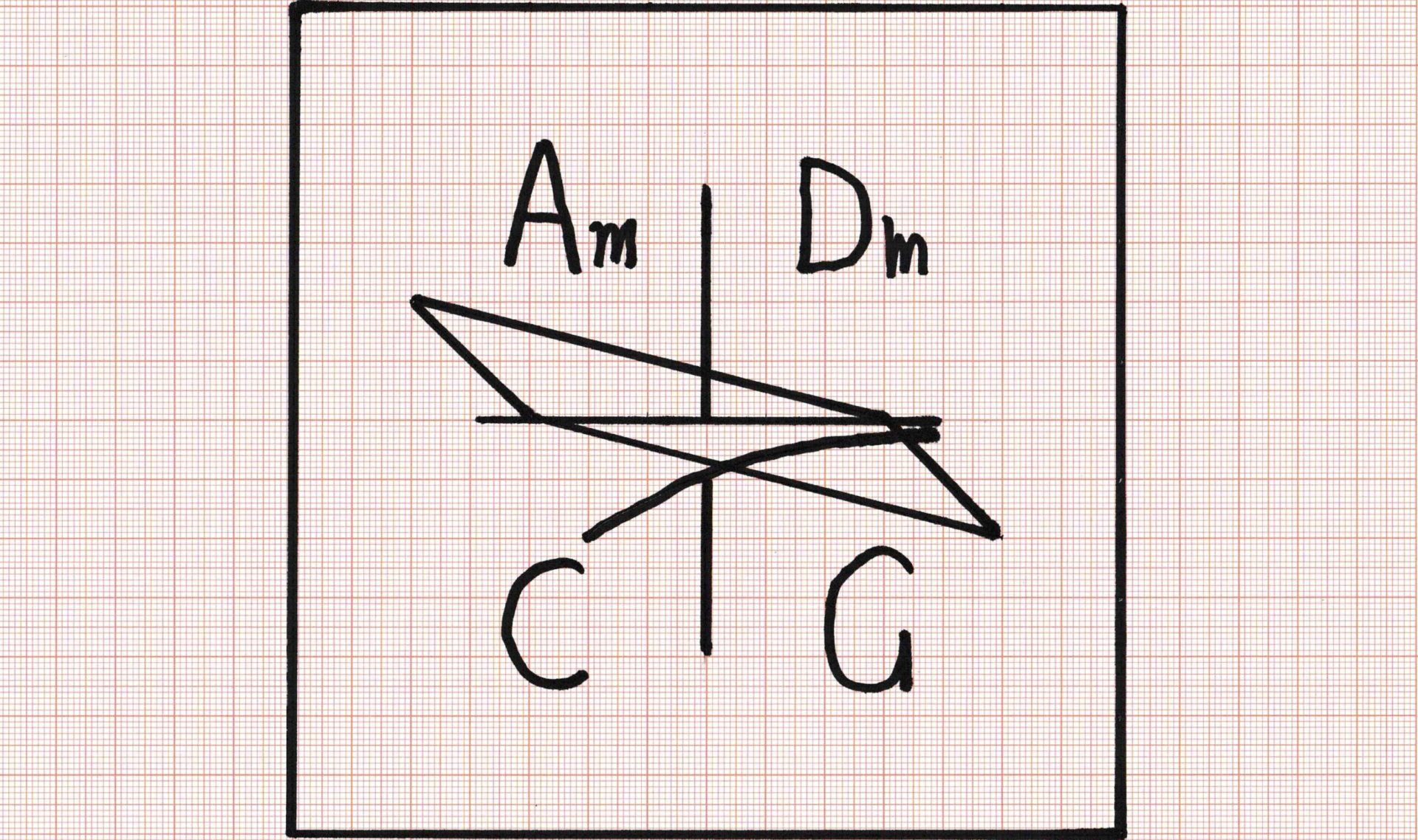

Zone C [0/12] C, Am, Dm & G chords

C COF

- This is the custom-made Circle Of Fifths 2.0 (COF) of C, including the number of flats or sharps belonging to the major key belonging to the green chord numbered with a blue 1, which is the home chord (HC) of the ionian mode of this Zone.

- The 7 bright green colored chords are always okay in this key/Zone.

- In very specific situations, you choose the only dark green chord.

- The other non-green chords can also sometimes announce or imply a modulation, so keep an eye on the harmony.

- The 11 yellow colored chords are sometimes borrowed from outside into this key.

- The 5 orange colored chords are also, albeit rarely, borrowed from outside into this key.

- The last 12 red chords are hardly ever borrowed from outside this key, unless they belong to or help modulate to another key.

C Zone

You have arrived at your destination in Alphabet Music City! You are currently in the C Zone. Each Zone in AMC (Alphabet Music City) is the complete and unique area with scales (Aurs), chords (also in their Clocks) and a custom-made COF 2.0 (just shown above) to tie everything together.

- Notes of the green route are always in tune with the bright green chords of the COF 2.0, especially the notes in yellow because they belong to the pentatonic scale (PentAur) of this Zone.

- Notes from the red route are normally played in conjunction with the HC of the natural minor key, which here is the Am chord.

- The 4 notes of the 4 main chords in this Zone – which are also on the Clock below – are shown in lilac diagrams (In all Zones the lilac diagrams of the I chords are only clearly visible on the poster, or on the complete map of AMC).

- For other chords and Aurs, it is best to check the relevant pages or chapters here.

C Clock

- The I chord written in green letters and numbers is the HC of the ionian mode of this Zone.

- The numbered chord notes per quarter can be played in or over their corresponding chord.

- The chords followed from bottom left (I), to top left (VI), to top right (II), to bottom right (V) and again to bottom left (I) form a logical whole, but how many you use and their sequence, possibly in combination with the other ((bright) green) chords from the COF 2.0, is up to you of course.

- The 3 standard notes of the shown 4 triads I, II, V and VI are always underlined.

- The Melo (the note that can enhance the melody) is orange, the Blu (the only real blue note per Zone that may come as a surprise) is light blue and the red notes in the V quarter combine to form a SharpAur/[**] from another Zone that can be played in or over an altered V quarter chord.

- Check out other pages/chapters on the Aurs and Clocks to find out what the Aur icons in the quarters of the Clock stand for and how to use them.

- The DeltAur, indicated by the square with the green letter Δ in it, contains the same musical notes as the green route in the Zone above.

- For the other 6 Aur icons, and their musical notes, I would like to refer you to the relevant pages or chapters.

- Under the Clock, you will often find a musical mode indicator that is also explained elsewhere later.

4 Main triads of the 4 quadrants of the Clock:

I: CEG

VI: ACE

II: DFA

V: GBD

Aurs of the Zone(/Clock):

[Δ]: CDEFGAB(C)

[P]: (A)CDEGA(C)

[*]: ABCDEFGis(A)

[**]: ABCDEFisGis(A)

[B]: DFGGisAC(D)

[[]]: GGisAisBCisDEF(G)

[U]: GABCisDisF(G)

I always close the general Zone, Clock and COF information with the 7 Aurs and 4 quadrant triads applicable to that Zone and Clock. In addition to 5 unique Aurs per Zone, namely the DeltAur [Δ], PentAur [P], StarAur [*], SharpAur [**] and BluAur [B], the Zones share some SquarAurs [[]] and UpAurs [U] with each other. For the how and why, please read the relevant chapter. There are only 3 flavors of SquarAur ([[]]) that you can recognize by the red, white (in black), or blue letters. You can recognize the [[]] that contains at least EsE/DisE by the red letters. You can recognize the [[]] that contains at least CisD/DesD by the white letters in a black field, and the [[]] that contains at least DDis/D’Es’ by the blue letters. There are even fewer UpAurs ([U]), namely only 2, with which all ‘whole-tone’ scales are formed in music. You can recognize the [U] that contains at least the passage EsF/DisEis by the green letters in the blue areas, and the [U] that contains at least the notes EFis/EGes by the blue letters with the green background.

Characteristics of this [0/12] C Zone are: the notes of the major scale of C are all white keys on the piano and are easy to find and touch, and therefore the easiest to use for that instrument. Not entirely coincidentally, these notes on sheet music are also without flats or sharps and are therefore easier to read and apply than those with those signs. Also, 6 of 7 diatonic chords in C can be played on the guitar with so-called open chords. The C, Dm, Em, G, Am, and Bm-5 can all be played as open grips, so that only the F grip needs a so-called barre grip. Open means that at least 1 open string is used, and on this string no note is thus pressed in in between frets. Also, all strings on a (bass) guitar are all ‘white keys’ notes, which are therefore also without flats or sharps on sheet music. However, strictly speaking, the Bm-5 (or Bm7-5) is not a true open chord because it basically does not use a single open string. And the F can also be played without a barre (you have to have flexible hands for it), but then it is still played without an open string. These last 2 C diatonic chords can at least be played without that somewhat more difficult barre grip and are therefore “open” in that sense, and they also consist of only “white key notes”. Now, it must be said that C does not mean or sound the same on every instrument. When an alto saxophonist talks about: ‘I play a C’, it sounds, and you will find it like an Es on a piano or guitar. But the instruments tuned in C that you can find everywhere are: the piano, other keyboards, and (bass) guitars, which are always tuned in C, and those are really the most used overall. So here I would like to propose that whenever musicians or theorists talk about a C, everyone should know that, for 90% of the time, we are talking about the standard sounding C. It is a pity that the rest, on their apparently different tuned instruments, have to find out for themselves which replacement note they will read and thus have to play to sound the same as that C. For the record: I, like most musicians of Western music, assume that C is obtained by equal temperament* tuning. In standard tuning, one C is always a minor third above A = 440 hertz. *(Wikipedia: ‘In classical music and Western music in general, the most common tuning system since the 18th century has been 12 equal ‘temperament’ (also known as 12-tone equal ‘temperament’), which divides the octave into 12 parts.’)

It is also inevitable that a lot of music seems to revolve around that C (see, for example, my analysis of Milestones) because:

1. C and his accompanying major scale are very accessible, especially on piano, and

2. The C is the root note of that major scale, and most music is in some derived major mode or its Aeolian cousin, the relative (A) natural minor. Moreover, the C and Am shared scale and 7 diatonic chords are often one of the first things you learn on your guitar or piano. So it becomes an automatism first to grab it (/by default) and apply it in your practice routine and/or new creations; being in C/A minor feels safe and is best known! But that can, of course, also hinder your creativity and originality. The keyboard players among you will have an easy time in this chapter, while the guitarists and saxophonists, for example, will have to put in some effort to play the right notes in this key of C. On the piano, that is all 7 large white keys, but on guitar, only all open strings, but then the easiest notes for the guitarists kind of end after that a bit. On an alto sax, you should use the fingerings A, B, Cis, D, E, Fis and Gis from low to high. So on that sax you already play with 3 sharps in A major, while the (bass) guitarists and pianists (can) play in C major without flats or sharps, and the latter therefore do not read those signs on sheet music. An advantage for the guitarists is that to play the 4 chords C, Am, Dm and G of the © Clock*, they can all be played with so-called open grips. *This is actually superfluous and notated twice, because, to indicate which Clock you are talking about, you put the root note of the I quadrant chord of that Clock in brackets. However, ‘Google documents’ just happens to turn a parenthesis-C-parenthesis (=(C)) into a ©. Let me immediately list all 12 Clocks described in that way. The clocks of C, F, Bes, Es, As, Des, Ges (or Fis), B, E, A, D and G, respectively, are also notated as follows: © (or (C)), (F), (Bes), (Es), (As), (Des), (Ges)/(Fis), (B), (E), (A), (D ) and (G). Of course, it depends on the context, because I can also mean a single note that I mention in parentheses. We treat (Ges) and (Fis) here as the same sounding Clock ((Ges)=(Fis), in terms of the pitches of the actual notes). These 2 ‘major keys’, based on these 2 roots, sound the same, but their key signatures are respectively noted on sheet music with 6 flats or 6 sharps. However, the roots, and thus all individual diatonic notes of their differently notated major keys, are enharmonic. By the way, the chapter numbering simply continues after this, but I didn’t want to give the Zones, which all have a unique identifying number [0-12], another chapter number, 15, 22, or so. Here, as well as on my site, aurzones.com, I can just ask you to go to the [0/12] C Zone or [5] Des Zone (in this part I) and you’ll all find them under that name and number. Now for the first few SOTS.

🦉Old And Wise (Alan Parsons Project) – Am

[Δ] & [*] |C| & |Es|, modes A & C aeolian – Link: https://youtu.be/qVO2g4egHAQ ) Link Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_and_Wise ⇋ ‘Old and Wise’ is a power ballad by the Alan Parsons Project from the album Eye in the Sky, released in December 1982. Vocals: Colin Blunstone (The Zombies). The song starts with a nice orchestral intro in which the theme is played, which is repeated by the piano under verse 1. After the modulation to Cm, the orchestration returns in the chorus section. This is repeated once to bring back the piano/orchestra theme one more time for the solo. The fade-out is after the main part of the saxophone solo, in which the orchestra accompanies. Yoni also says in the title of his video that it is a tutorial of this song, Old and Wise, but he simply performs the entire acoustic cover on guitar and vocals. So you have to look at his hands yourself and find out what the chords are. In this Korean video, ‘Old and wise’ (link: https://youtu.be/5AXaNhYTraQ), of ‘*hanunfa’, you can also follow the chords even though they use the capital ‘M’ for major seventh (_Δ7 ) chords. Plus, I suspect the chords are somewhat simplified, as I saw a sheet music version of it a long time ago where the chords looked a lot more complicated. So keep that in mind. The intro starts in the Am ks without flats or sharps with an Am, G6, FΔ7, Em7, and Dm7 in a certain order and ends with a fairly striking A major triad. That parallel ‘A’ major chord seems to want to take us somewhere, but it doesn’t because we just continue in the same Am key. Namely, the first sung verse repeats the same chords but uses the Dm7 as a transition chord to the chorus (apparently) in Cm. We finally leave the [C] Zone with the chords Cm, G7/B, Gm7/Bes, F/A, Fm7/As, Cm/G, D7, G7, Cm, Bes6, As, Cm/G, Fm, Cm/Es, D7, G7, Cm, Bes6, As, Cm/G, Fm, Cm/Es, D7sus4, D7, G7, As, Bes7/As, Gm7, Cm, Bes6, As and Bes7/As. But we end the chorus very surprisingly and beautifully in C with a C triad. As a result, we are modulated back to the original ks [C], but then to the relative C major of A minor. The whole thing is repeated until another A major triad comes at the end of a short repetition of the intro chords. After which, the sax solo erupts over part of the chorus chords. So there is a transition from a full A triad to the solo chords As, Bes7/As, Gm7, Cm, Bes6, As, Bes7/As, and C. The chords in bold show several things at the same time. The verses and instrumental parts in between seem to be in Am, but always end (in between) with a major A triad. The choruses and solo seem to be in Cm, but they always end (in between) with a C major triad. So the song is always switching between the [C] Zone and the [Es] Zone, and within those Zones from the aeolian modes to, albeit very briefly, the ionian modes. The parallel mode of C ionian is C aeolian (Cm), and of A ionian it is A aeolian (Am), so this song also goes through several parallel modes as well as relative ones. Also, the roots of the chords in bold show a reverse enclosure*, when, after the fact, the As and Bes roots enclose the A root. *Enclosure is when a certain surrounding note above and a chromatic note below the targeted note, or a note below and a chromatic note above, ‘enclose’ the target note. Other special features are the chromatically descending bass at the beginning of the chorus (see the red italicized chords earlier). By the underlined chords, you can recognize the regularly recurring ‘V of Vs’, where the D7 asks for the G7, which in turn asks for the Cm, with which it musically resolves to the tonic. Except the last time when ‘As’ follows G7, when the inevitable resolution to C is postponed, but eventually completed. What we can learn from this composition is that you can switch between relative and parallel modes, but you have to be careful with this, especially when you also realize another goal. Namely, here of the 2 relative A aeolian and C ionian modes, you also want to use their relative and even parallel keys or modes; modes, single chords, and/or keys at least change here from: Am↔A, C→Am, Am→Cm, A→Cm and Cm↔C. Of which, I personally like the A→Cm modulation to the sax solo the best because it happens so unexpectedly and beautifully with those aforementioned bold printed chords. That A chord is a bit of a decoration in the run-up to the sax solo because the sax already starts over it with the notes GCD|(Es), which are respectively the Dom, Flat and fourth relative to that A triad/musical key.

🌹Für Elise (Ludwig van Beethoven) – Am

[Δ] & [*] |C| & |F|, modes A aeolian & F ionian – Link: https://youtu.be/WsZdkdVzSnc link Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F%C3%BCr_Elise ⇋ A very special version of this classic Für Elise, namely the flamenco guitar version. The first part was and is also interesting here from the start with the changing chords Am, E(7), G, and C. The theme is mainly played with the [Δ] [C]. But the melody is embellished by a Blu Dis, which this piece in the [C] Zone borrows from the (G) Clock/[G] Zone, from the BluAur there. The diatonic E note alternates with this borrowed and very distinctive Blu Dis. I don’t think Beethoven knew about the existence of what people later came to call the blue note, and which I came to call much later the one and only Blu per Zone. The piece here, as in its original classical version, briefly enters the [F] Zone with an F and Bes chord. I haven’t examined the original score for all the precise chords, but there are plenty of them in this performance. These are, in order of first appearance, at least Am, E, G, C, E7, F, Bes (A#), Cm, A, Em, Dm, A7, Es (D#), and Besm (A#m). In that respect, classical music works/worked differently from our current music, and also differently from this flamenco-inspired version of Für Elise. I think they thought about music very differently then, more in themes and motifs and less in chords (schemes), than we do now since jazz, blues, and rock and roll (for example). Amplifying instruments (and now also being able to distort them) will also have something to do with this, which, just like in a classical orchestra, is traditionally done in a flamenco setting with larger numbers of the same instruments. Flamenco guitar music is also normally done with a semi percussive guitar playing style, cajón, clapping, and castanets. But nowadays, classical music is also performed with this and other (more) modern rhythm section instruments (for example, listen to the Dutch band ‘Fuse’ here: https://open.spotify.com/artist/1FayrEV2WYTH8tzkxkWZzP?si=BrxVHQNDSUyTYGuKMVp2ww). All in all, it’s nice to hear this fusion between traditional classical music and that other classic-like thing. If you look hard, you’ll probably find a metal version of it too, plus keep an eye on my Spotify account as I’ll hopefully be making a Marcus Miller-inspired slap & pop bass version of it with vocals soon. In terms of chord analysis, the piece mainly revolves around the V (A)-VI © tension arc. With not 1, but 2 tension-giving notes: the LT Gis in that E(7) chord and that Blu Dis from [G]. The bridge 1, here over a G and C chord, and bridge 2, over an F and Bes chord, give a nice change after hearing that tension between the Gis/A and Dis/E notes for a while. At the end, they go by all kinds of borrowed chords (including Bes(m) and Es) to end up back at the HC Am and its play with the Blu Dis and the E(7). It is always recommended to follow ‘Music Matters’ if you are specifically interested in composition and especially classical music, such as his special on ‘Inside the Mind of Beethoven’ here: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PL5j5H06QkhxHz5MOh02n2RcQJiMbURawD. One of the most beautiful classical pieces ever is Beethoven’s so-called ‘Moonlight Sonata’, which is also discussed there. In terms of modulations, that piece is a little bit similar to the previous (short) SOTS about ‘Old and wise’, but now from Cism to the relative E major, and then to the parallel Em, etc. Gareth Green of Music Matters already explains to you the first 16 bars of this sonata perfectly, because it would (for now) go too far for the SOTS objectives here to delve so deeply into a classical piece.

🎺So What (Miles Davis) – Dm

[Δ] |C|, mode D dorian (regular modulations a semitone up) – Link: https://youtu.be/qhLyI4xGWnA link Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/So_What_(Miles_Davis_composition) ⇋ In the video called ‘So What Jazz Chord Voicing Piano’, the creator of this video, PianoGroove, shows the piano part for this classic. The voicing is what is called the ‘So What voicing’, where a Dm11 is built here by mainly stacking fourths on top of each other. The sound of a chord built up in this way of ‘fourths voicing’ sounds more open than the same chord built up in thirds. The chord that is created by building it up in these largely fourth intervals, as indicated below between the notes, can still be called an _m11 chord. That, because it has the notes of the triad, the minor seventh, and the highest-mentioned extension, the 11th. Instead of playing DFACEG, you play D4thG4thC4thFmajor3rdA, dropping the bold printed red ninth, thereby making it a Dm11(no9). It may be useful to leave that out in some cases, because a similar ninth (E, still here) can get in the way of harmony. Namely, the cool trick used in So What is that the complete chord in ‘fourths voicing’ is preceded by playing all its notes a whole step higher. That whole-tone higher chord is then an Em11(no9). If instead you would still play the ninth Fis of this last Em11 chord, this chord note would no longer remain diatonic in D dorian because the Fis is not in [Δ] |C|. So for both chords, in addition to their fourths voicing, or precisely because of those fourths voicings, the performers or composers have chosen to omit the ninth. That was also possible because, in addition to the seventh, the highest chord note number 11, the root note, and the third were mandatory. With the Em chord, the B is clearly present as the typical D dorian sound. Every few bars, the same typical dorian sound is repeated, but a semitone higher with the Esm11(no9) and Fm11(no9) chords. These are the only 4 chords in the intro and theme sections, after which, in the solo section, the Dm(7) and the Esm(7) are the basis for it. So, few chords, but with a very beautiful quartal voicing, in a piece of music that is also very recognizable by the question and answer game between a beautiful bass line and these chords. A good and beautiful song to hear the (D&’Es’) dorian mode, and if you perform it yourself, to practice it. The video further explains how to build up the chords, practice them, and apply them. The melody and solo parts on Miles Davis’ So What recording are quite a study in themselves, which unfortunately we will not do here. Fun, in terms of learning how to solo over it yourself, might be the video ‘Soloing On “SO WHAT”‘ by Aimee Nolte Music (link: https://youtu.be/9LED6mNH1Dc). She, together with Kent Hewitt on YouTube, is very interesting for the jazz players or jazz enthusiasts among you. I also wanted to discuss in a separate SOTS the chords Dm, G, F, C of ‘Another Brick In The Wall, pt 2’ by Pink Floyd. But it turns out you can play the Em11(no9) and Dm11(no9) over it in the style of the So What piano chords. This song by Pink Floyd also has such a distinctive D dorian sound, especially because of that G chord, because the characteristic D aeolian Bes note is missing in its chords.

🛸Tommy Is An Alien (Hans J.C. Bakker [c’est moi!]) – G mixolydian

[Δ] |C|, mode G mixolydian (major third blues in G) ⇋ I have written* a blues in G7 myself that I want to record and release on Spotify in the foreseeable future. It is a simple blues with 4 bars of G7, 2 bars of C7, 2 bars of G7, 1 bar of D7, 1 bar of C7, 1 bar of G7 and 1 bar of D7. *In my case, writing this blues mainly involved making up lyrics and melody, but I also modified the standard chords a bit. Here on the left, you can see what I play for the first four bars, i.e. the blue GBE notes from low to high are my guitar grip that I keep coming back to. But I always start the 4 measures of “G7” on beats 1 and 3 with the red notes F and Ais on top of the blue notes GB which can sound normal. I don’t touch the low E and A strings anyway, and the high open E string does sound when I don’t play the red notes. As a result, the E on the B string and the open E string regularly sound together [so I have to tune well!]. Per beats 1-4 and the 4 so-called ‘ands’ I play the following notes:

1: GBFAis – and:_ – 2: GBEE – and: _ – 3: GBFAis – and: GBEE – 4: _ – and: _. This is also the rhythm for the upcoming chords. So what I play alternately is a G7+9(no5) and a G6(no5). After 4 bars of these G chords come 2 bars of C7 with a similar construction. The basic grip on the 2 and ‘and’ of 3 are again the blue notes, BesDG in this case. But on counts 1 and 3, I also play the red notes E and A over that on the B and high E strings, respectively. As a result, in the latter case, first the BesEA notes sound, and then BesDG again and again. No open strings further here. In fact, I then play a C13(no5,no1) and a C9(no3,no1) in turn, assuming that the other instruments can/will play the root note (etc.). After this, I go back two bars to the G chord construction. In the 9th bar, I play the same thing as I did with the C construction, but now everything is 2 frets higher. So in that bar, I alternately play D13(no5,no1) and D9(no3,no1), see ‘D7’ picture. Bar 10 is the C chord duo again, like before, after which I go back to my standard G chord duo for bar 11. In bar 12, a more familiar guitar chord grip is finally played, namely this D7+9(no5) on the right. No extra red notes or open/double-sounding strings here, just a strong chord wanting to resolve to a G7. This is my attempt to spice things up a bit in terms of chords in a standard blues, using mostly the BluAur [F], as I sing the following lyrics:

Tommie Is An Alien

Tommie is an alien,

Flying through space and time.

Maybe you think it’s strange,

But he’s more than a friend of mine.

There ain’t nothing he can’t do!

Tommie is an alien.

Tommie’s in a color blue.

He wears nothing but his own skin.

Maybe you think it’s bizarre.

(But) He’s as blue as the skin he’s in.

And when life brings him down,

Tommie’s in a color blue.

When he flies his spaceship,

Or with his wings,

His tail is wagging, happy.

It’s just one of those things.

That is Tommie,

Tommie the alien.

And that’s my story for you.

I tell you, it’s true!

We have now had one Zone and seen that many chords are already being borrowed in the 4 SOTS that passed by. That is also the reason why I chose those songs, except for that last blues, of course;-). Needless to say, I also searched for an interesting song in C major/C ionian mode, but either they were in a different mode of C, or, chordwise, they were not interesting enough for a SOTS. Here I am going to discuss plenty of other songs that are in the major key/the ionian mode, but then you will also see that there will be a lot of outside borrowing, just like in songs with a minor third in their HC. So this is the method by which I hope to show you how to build chord progressions and how to enrich them with modified and/or borrowed chords. Later in Part II and further, we will also look at how your use of Aurs and other tools can enhance your experience and/or creation of music. Jake Lizzio has another very educational video on ‘Writing [chord] progressions with borrowed chords’ here: https://youtu.be/7IdttvJSedg. Among other things, he talks about borrowing 1 or more chords from a parallel mode, in C from the parallel C minor mode, for example. Doing that can, in theory, immediately sound much more unique than using your standard diatonic chords, which everyone already uses. He points out to us: when you’re thinking of borrowing a Bes chord from the diatonic chords in C aeolian, while originally being in the C ionian mode, that that chord can also come from the C mixolydian mode. There is a subtle difference here. Time to change Zone to our next-door neighbor, and thus to go to Zone [1] to the left of |C|. Let’s go to |F|!